featured artists

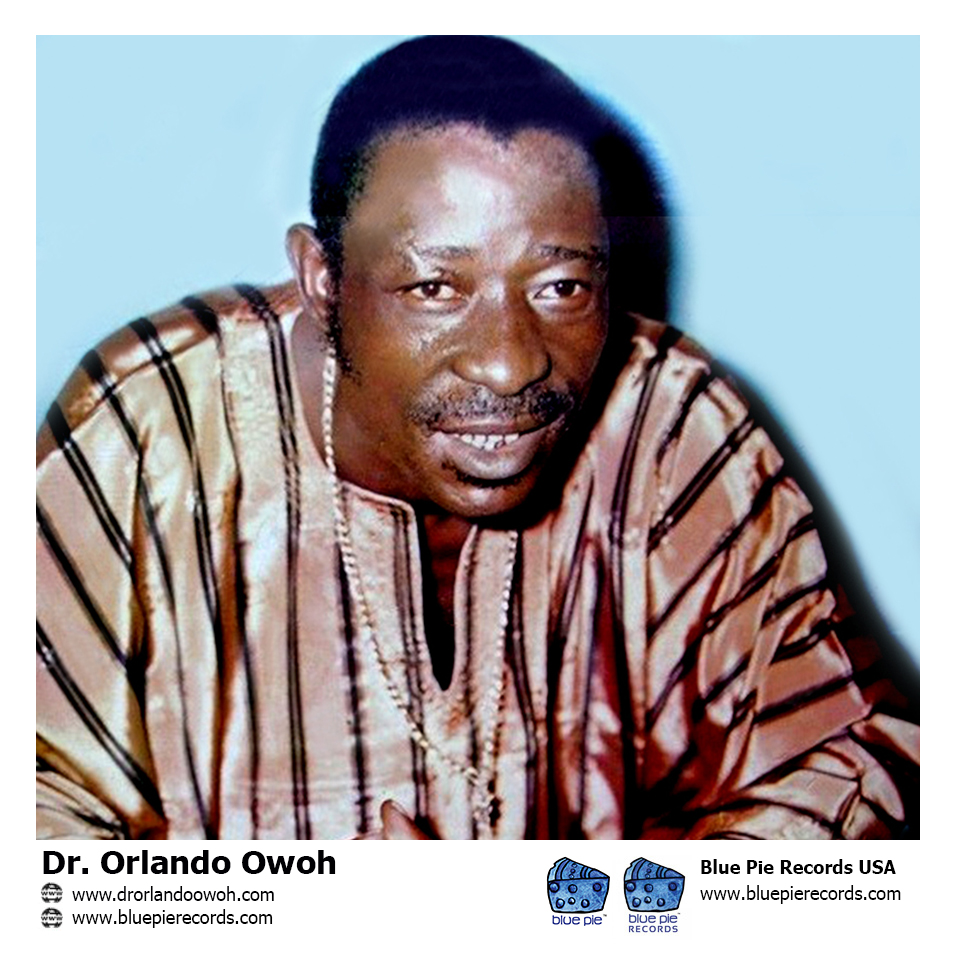

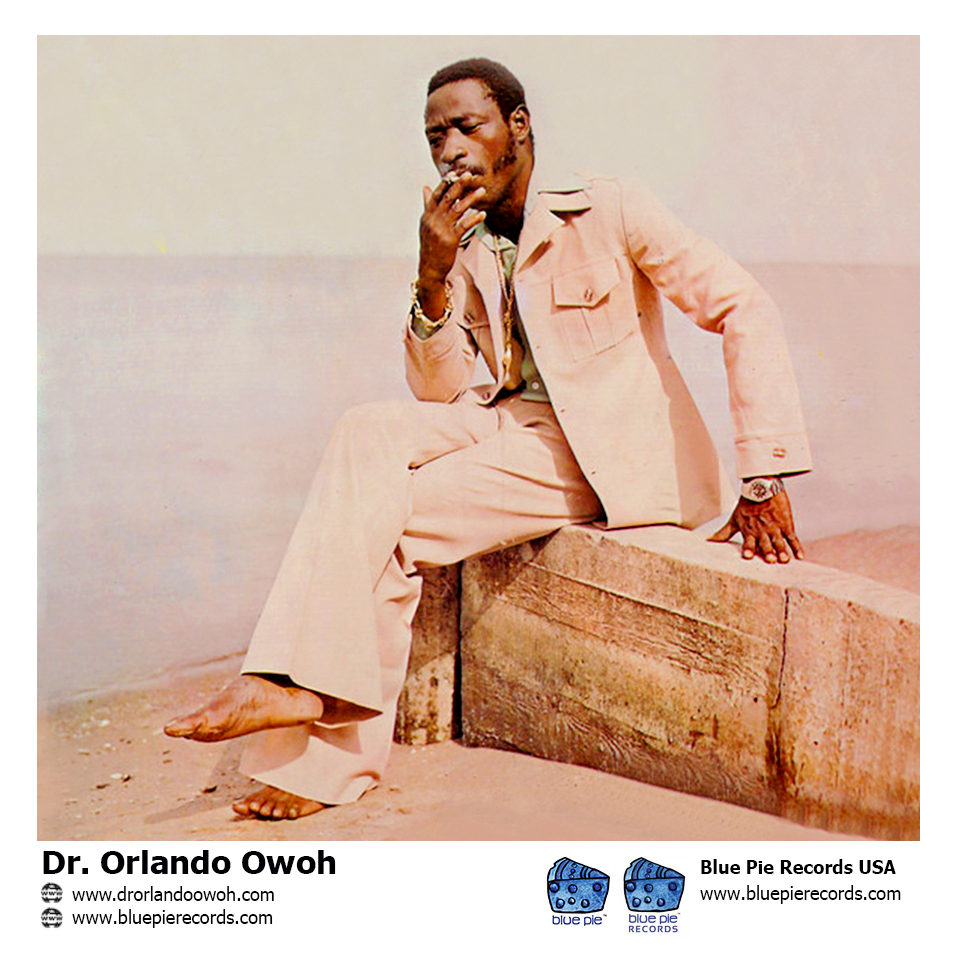

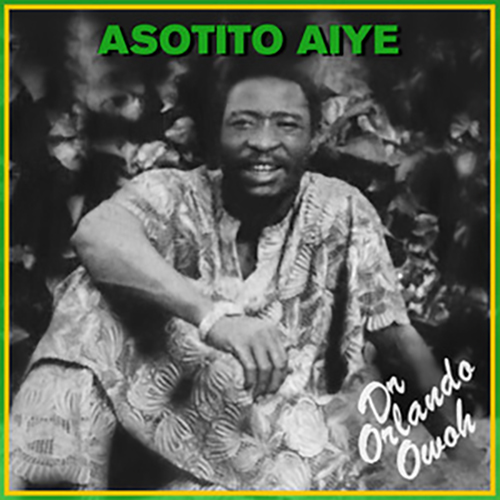

A household name in Nigeria, Dr. Orlando Owoh enjoyed a durable popularity that has cut across generational lines in his home country and beyond. Leading groups such as the Omimah Band, the Young Kenneries, and the African Kenneries International, Owoh remained popular even as Nigerian tastes shifted to the newer Juju and Fuji styles! Before this transition, the hot style in Nigeria and Ghana was called Highlife. It developed from a traditional Yoruba genre called “palm wine music”, overlaid with danceable guitar rhythms, and, in the hands of many musicians, it also contained a strong element of Trinidadian calypso. Owoh combined this aesthetic with a traditionalist spin on things to make his own brand of excellent sound. His story, like that of many musicians, is a progressive journey in which we can see his choice in musical trends shaping in response to the events in his life. He travelled far in the music world before his passing, and is remembered to this day even outside of his devoted Nigerian fans.

A member of the Yoruba ethnic group, Owoh was born as Oladipupo Owomoyela in Nigeria’s Oyo state. Some publications have assigned Owoh’s birthdate to the early 1940s, but Nigeria’s P.M. News (in an article reproduced by the Africa News online service) reported that Owoh celebrated his 70th birthday on February 14, 2002, and a 2005 report in the Nigerian Sun tabloid gave his age as 73. Owoh’s father was a carpenter who was known around the town of Osogbo as a good part-time musician, but he greeted his son’s growing interest in music with little enthusiasm.

The family moved frequently from place to place, but Owoh sought out musicians and formed bands in each place they landed. Owoh’s father insisted that Owoh learn a trade as a condition of being allowed to work on his music, and Owoh obediently apprenticed himself to a carpenter. “I learned fast,” Owoh told Tosin Ajirire of Nigeria’s Daily Sun. “A trade that would take my contemporaries four or eight years to learn, I mastered in only six months. So, having satisfied my father, he couldn’t help but bless my choice of career.”

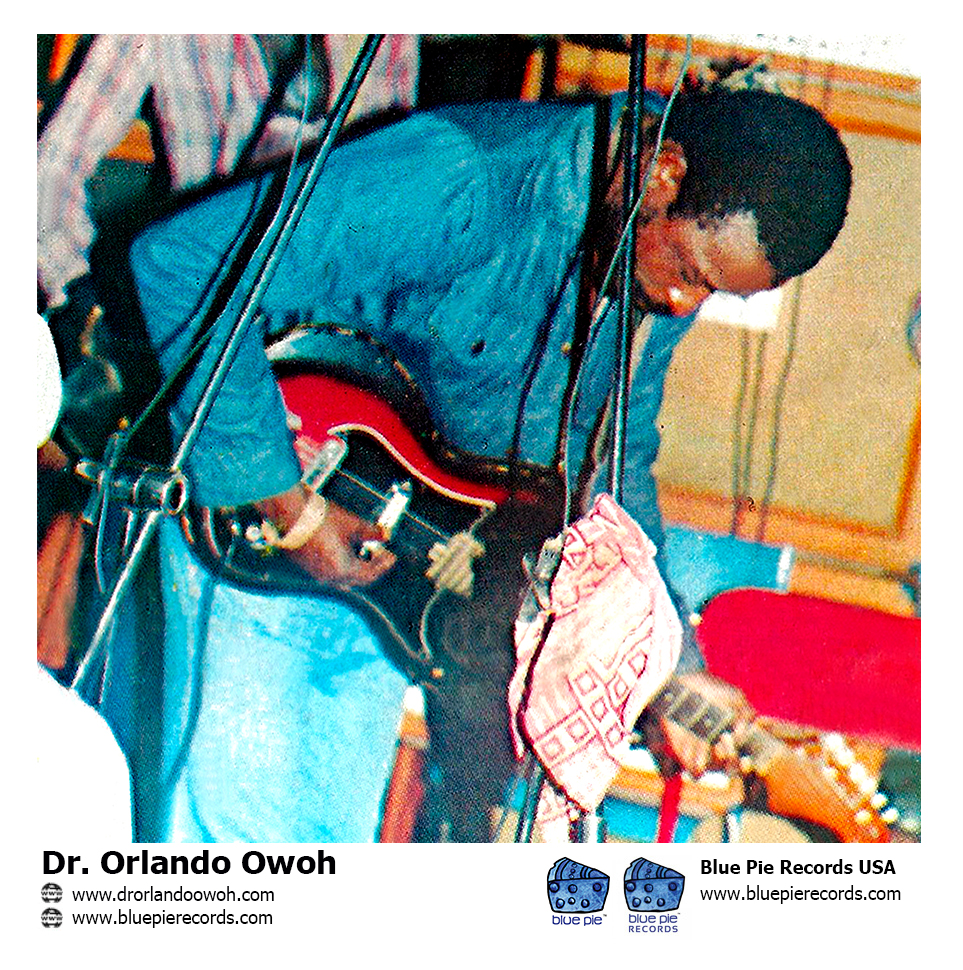

Owoh’s first big break came when he was hired as a musician by Nigeria’s Kola Ogunmola Theatre Group, one of the country’s first theatrical troupes. Owoh played drums and sang with the group when England’s Queen Elizabeth visited Ibadan, Nigeria, in 1956, and he continued to perform plays mounted at the University of Ibadan. Performing with several bands, including one called Akindele (or Dele Jolly) and His Chocolate Dandies, and in another called the Fakunle Major Band, Owoh realized that music in West Africa was developing in a new direction, and sought out lessons on the electric guitar from musician Fatai Rolling Dollar.

In Owoh’s music, the sophisticated Caribbean-style horn arrangements of Highlife were deemphasized in favor of Owoh’s guttural voice, guitar, percussion, and down-to-earth lyrics. Owoh formed his first group “Orlando Owoh and His Omimah Band” around 1960, and quickly recorded their first single, “Oluwa, lo ran Mi” (“God has sent me”) on the Nigerian branch of the Decca label.

Owoh’s grassroots take on Highlife music led him into political realms in the turbulent Nigeria of the 1980s. Ronnie Graham, in The Da Capo Guide to Contemporary African Music described his music as featuring “saucy and provocative lyrics,” and Owoh apparently ran afoul of the Nigerian government. He was also imprisoned for six months on cocaine possession charges. Graham, in his book The World of African Music,) noted that Owoh was “associated in the public mind with various forms of drug abuse,” but Owoh later denied the charges.

“I cannot forget the experience. It’s so painful,” he told Ajirire. “They say I sniff cocaine, it’s a lie…. Do I smoke Igbo [marijuana]? No, I don’t smoke Igbo, what I smoke is Ajuwa. Ajuwa is our local herbs.”

Despite this pain, he continued practicing his craft, and he accomplished what he wanted in the first place – his music was noticed, and not just because of the political allegations, but because of his talent captivating those around him.

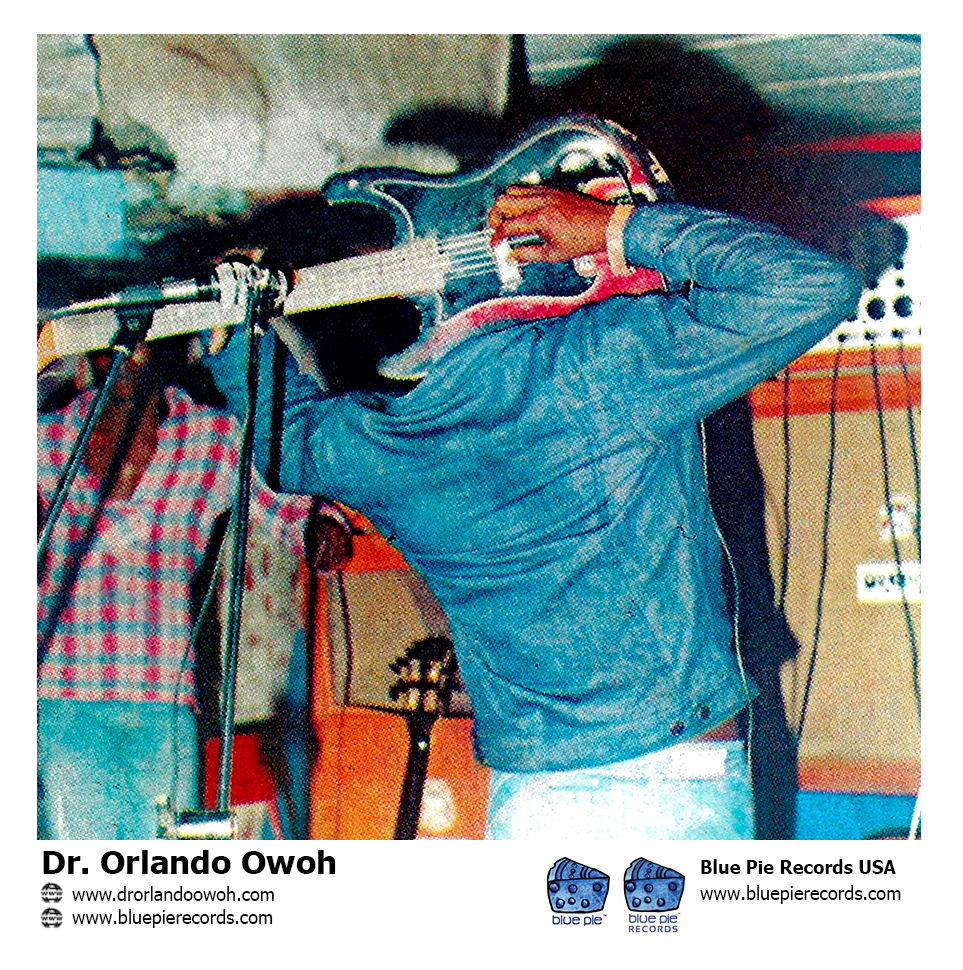

It’s a thrill for any musician to hear his or her record being played on the streets for the first time, but Owoh’s experience was more thrilling than most. “I almost died the first time I heard my record,” he told Ajirire. “I was passing along Idi Oro in Mushin and suddenly I heard my record being played in a shop across the road…. Without looking at both sides, I dashed across the road and ran towards the shop. I heard a car screech to a halt; it almost crushed me to death.” The enraged driver pursued Owoh into the shop, but calmed down when Owoh pointed out that he was the musician heard on the recording.

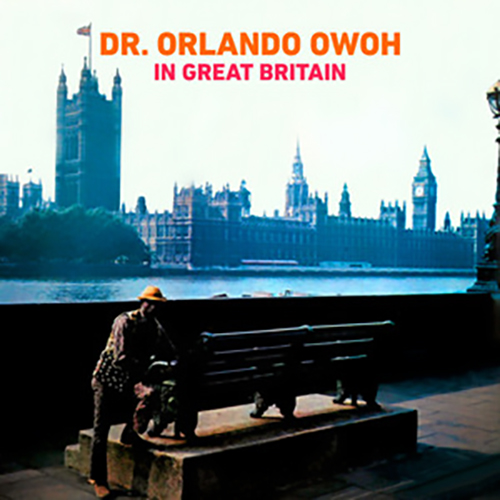

Owoh notched several hits in Nigeria in the 1960s, but his career was slowed between 1967 and 1970 by the country’s civil war. Owoh fought for the Nigerian government against the country’s Biafran rebels. After the war he recorded a major hit called “Oriki Ilu Oke,” and his fame spread to Nigerian expatriate communities. In 1972 he played in London, England, at a graduation ceremony for Nigerian law students, and went on to perform on a larger bill that included South African legend Miriam Makeba. “I played at the African center on October 1, 1972. That was where I was honoured with the doctorate degree in music,” Owoh told the NigeriaArts website. From then on he was often known as Dr. Orlando Owoh.

Gaining fans as a result of these initial appearances, Owoh toured the United Kingdom and appeared in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Italy. He also performed in the United States in the 1980s and 1990s, but although his music was widely available in Britain, he enjoyed only one U.S. release, Dr. Ganja’s Polytonality Blues, a 1995 reissue of earlier Omimah Band and Young Kenneries tracks. Back in Africa, Owoh’s LP albums on the Decca, Electromat, and Shanu Olu labels were consistent hits. He eventually gave up trying to keep track of the number of releases, but estimates have placed it above 40.

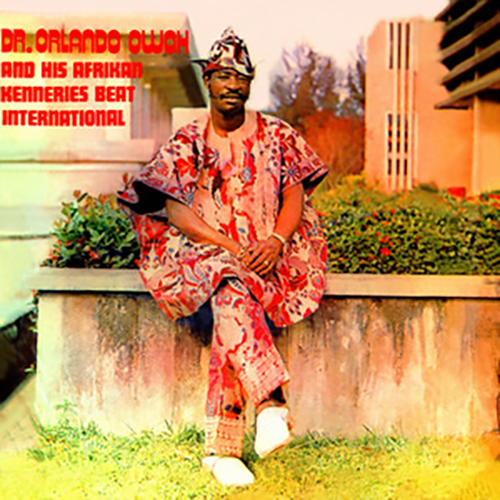

Around 1975, Owoh named his backing group “His Young Kenneries”, a term that later changed to “His Africa Kenneries International”, or “His African Kenneries Beats International”. The word “Kennery,” (also spelled Kenery or Cannery) seemed to be related to the word “canary.”

“They say my voice is unique like that of a bird called Cannery,” Owoh told Ajirire. “And in truth, if you see Cannery, it has the colour of a rainbow and its voice has different tunes.”

As Western production electronics began to infiltrate the music of other West African bands, Owoh stuck to his low-tech approach. Dubbed the “King of Toye” as he created his unique musical mix, Owoh entered each of his decades of performing with his prowess and popularity undiminished. Heard today, his music sounds distinctly more traditional than that of other Highlife bands and strongly evokes the music’s rootsier base. He also generally remained true to the small guitar-band format of Highlife, rather than adapting his style to the huge, kinetic ensembles of the rising juju genre of King Sunny Ade and his African Beats, although some of his records were designated as Juju on their printed labels. He sang mostly in Yoruba, but recorded music in English on occasion. His recordings, like those of other African musicians, consisted of long, dance-suitable medleys of connected pieces; they gave only a small slice of what would occur during an actual Owoh performance, which might last all night.

Dr. Orlando Owoh left his mark on the world in multiple ways. To Nigerians and Ghanaians, he will not be forgotten for his contributions to their culture, and his reinvention of existing genres and trends. To the political world, he will not be forgotten for how he stood against the establishment. And of course to the music world, he will never be forgotten for how he united the planet under songs that Africa should be proud of. Like a proud canary, his songs elevated the world to a height that can never leave us.